Hanukkah Celebrations and Traditions

The Hanukkah Miracle

The story of Hanukkah is about the victory of an army of Jewish fighters, known as the Maccabees, over Hellenic emperor Antiochus IV’s supporters who desecrated the Temple in Jerusalem and built an altar to the Greek god Zeus there.

After the Maccabees reclaimed the Temple and Jews were preparing to rededicate the holy space, they realized there was only enough oil to last one day. Determined to begin the repairs, they lit the menorah and it miraculously burned for eight days, allowing them all the light they needed to finish their work. This is the reason Hanukkah menorahs have eight candles.

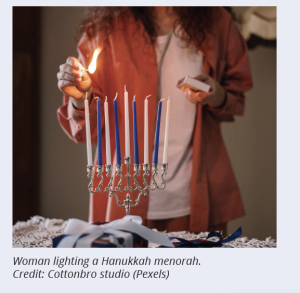

The miracle of the oil is celebrated with the ceremonial lighting of the hanukkiah, the nine-branch candelabra used only at Hanukkah. The hanukkiah, also called a menorah, holds eight candles, one for each night of Hanukkah, plus one known as the “shamash,” which means the servant or helper candle used to light the others.

Hanukkah begins on the 25 Kislev on the Hebrew calendar. This year, Hanukkah begins at sundown on December 18.

How to Light the Hanukkah Menorah

Each night of Hanukkah, a new candle is lit using the shamash candle which means servant or helper.

On the first night of Hanukkah, a candle is placed on the far right side of the menorah and lit with the shamash.

On each subsequent night of Hanukkah, an additional candle is placed to the left of the previous night’s candle and is lit first, then all candles present in the menorah are lit from left to right. This is done so that the lighting begins each night with the newest candle.

By the last night of Hanukkah, all candles will be glowing.

The Latke Variations: Move Over Potatoes

By Linda Morel

(JTA) In Yiddish, the word latke means pancake. The definition doesn’t include a connection to potatoes. After consulting Webster’s Dictionary, it was confirmed that a pancake is a thin, flat cake of batter fried on both sides on a griddle or in a frying pan.

Although Ashkenazi Jews are famous for preparing latke batters with grated potatoes, the tuber is a relatively recent addition to their culinary repertoire.

Originating in South America, potatoes were unknown in Europe until the 16th century, when explorers brought back tuber shoots from their travels. Once planted, these shoots grew abundantly throughout Eastern and Central Europe, where produce was sparse during harsh winters. Potatoes became an inexpensive crop to farm and arose as a staple of the Ashkenazi diet.

Although potatoes have proven to be a superior latke ingredient, here are some others to enhance the Jewish pancake genre.

BASIC FLOUR LATKES

Yield: 8 latkes, 4 inches in diameter

Ingredients:

Ingredients:

3 tablespoons butter for batter, plus 2 tablespoons, or more, for frying

1 egg, beaten

1 teaspoon plain yogurt

1 1/4 cup 2 percent low-fat milk

1 2/3 cups flour

2 1/2 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

Preparation:

1. In a small pot, melt 3 tablespoons butter. Cool briefly.

2. In a large bowl, beat egg, yogurt, milk, and melted butter, until foamy.

3. Sift flour, baking powder, and salt into egg mixture.

4. With a wooden spoon, stir ingredients until well combined.

5. Melt 2 tablespoons butter in a large (12-inch diameter) skillet, preferably the no-stick variety, until butter sizzles but doesn’t burn.

6. Pour half a soup ladle of batter at a time into hot pan. When bubbles appear in batter and bottom surface turns golden brown, flip pancakes. Turn only once. Gradually add more milk to batter if it thickens while first batch cooks. Add more butter to pan, if needed.

7. Serve pancakes immediately. If making several batches, pile pancakes onto an ovenproof dish and keep warm in a 200 degree oven until ready to serve.

Latke Variations

BANANA LATKES

Mash 1 banana (preferably over-ripe) with a fork until mushy. Add banana to step 3 of Basic Flour Latke recipe and follow remaining directions. Serve with maple syrup and chopped walnuts.

CREAMY LEMON LATKE

To step 3 of Basic Flour Latke recipe, add 1/2 cup whipped cottage cheese, 1/2 teaspoon vanilla, 1/2 teaspoon lemon zest, and 1 teaspoon sugar. Follow remaining directions. Sprinkle confectioner’s sugar over top of latkes and serve with black cherry preserves.

TEX-MEX LATKES

To step 3 of Basic Flour Latke recipe, add 1/2 cup canned cream style corn, 2 minced garlic cloves, 1 tablespoon minced roasted red pepper (from jar), 1/2 teaspoon ground cumin and 1/2 teaspoon chili powder. Fry latkes in peanut oil and follow remaining directions. Sprinkle freshly minced cilantro on latkes. Serve with sour cream.

PUMPKIN LATKES

To step 3 of Basic Flour Latke recipe, add 1/2 cup canned pumpkin, 1 tablespoon brown sugar, 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon, 1/4 teaspoon nutmeg, 1/4 teaspoon ground cloves and 1/4 teaspoon cardamom. Follow remaining directions. Serve with butter pecan ice cream.

CHOCOLATE LATKES

To step 3 of Basic Flour Latke recipe, add 1/2 cup chopped semi-sweet morsels and 1 tablespoon granulated sugar. Follow remaining directions, but fry on a medium-low flame so chocolate doesn’t burn. Serve with warm chocolate sauce (or melted semi-sweet morsels) and vanilla ice cream.

Hanukkah’s Sweet History

By Deborah R. Prinz

(JTA) Money and Hanukkah go way back, all the way back to the victory of the ancient Maccabees over the Syrian Hellenists. The foil-covered chocolate gelt recalls the booty distributed by the Maccabean victors, including coins to Jewish widows, soldiers and orphans, possibly at the very first celebration of Hanukkah, when the Temple was rededicated in 165 BCE.

In ancient Israel, striking, minting and distributing coins expressed Hanukkah’s message of freedom. As the book of 1 Maccabees (15:6) records, Syria’s King Antiochus VII said to Simon Maccabee, “I turn over to you the right to make your own stamp for coinage for your country.”

One of those early Israelite coins, produced during the rule of Antigonus Matityahu (40-37 BCE), the last in the line of Hasmonean kings (descended from the Maccabees), portrays a seven-branched menorah (candelabrum), a reminder of the centrality of the ancient Jerusalem Temple to the Jewish people and the victory of the Maccabees over the Hellenists. It represented political independence and religious freedom.

In the sixth century, the legal text known as the Talmud taught that the poor must light Hanukkah candles even if they had to wander door to door to beg for change to pay for the lighting materials, which in those days were probably oil, clay lamps, and wicks. Centuries ago, Yemenite Jewish children were given coins to purchase sugar and red food dye for concocting a special Hanukkah wine.

The first recorded appearance of the word gelt may have been in 1529, and it came to be identified with Hanukkah money. Giving gifts of coins at Hanukkah had become customary. The Hebrew word Hanukkah, which refers to the rededication of the Jerusalem Temple, also came to be associated with the Hebrew word for education, chinuch. Gelt supported Jewish learning.

In the days of the founder of chasidism, the Ba’al Shem Tov (1698–1760), rabbis often traveled to distant villages to give instruction to impoverished and illiterate Jews, generally refusing payment. At Hanukkah time, the instructors accepted coins and other tokens of gratitude. Not so long ago, coins were the only gifts bestowed at Hanukkah.

Opinions differ about how chocolate came to be associated with coins for Hanukkah. According to Tina Wasserman, food writer for Reform Judaism magazine, 18th- and 19th-century Jews became prominent in European chocolate making and started the Hanukkah chocolate coin custom. But Jenna Joselit, in her book, “The Wonders of America,” notes that with the increased purchasing power in the American Jewish community in the 1920s, Loft’s, an American candy company, responded by producing Hanukkah chocolate.

More on this topic can be found in Deborah R. Prinz’s book, “On the Chocolate Trail: A Delicious Adventure Connecting Jews, Religions, History, Travel, Rituals and Recipes to the Magic of Cacao” published by Jewish Lights.

Latest Posts

Krasoff Jewish Family Service Building Opens Soon

By Rabbi Amy B. Cohen Shalom Austin Jewish Family Service is thrilled to be opening their central office later this summer on the Dell Jewish Community Campus. The beautiful new building will house over fifteen staff members including counselors, case managers, the...

Next Step Foundation’s Upili Program Is Impacting Youths with Disabilities in Nairobi

Team Upili from left to right: Peter Simiyu, Carla Birnberg and Mariam Ndegwa at Joytown Special School in Thika, Kenya. Credit: Carla Birnberg For the past four years, Chief Storyteller for the Next Step Foundation, based in Austin and Nairobi, Carla Birnberg's...

Inspiring Jewish Journeys across a Growing Greater Austin

As I write this column, the school year is ending, and preparations are underway for the summer season and camp. I am also preparing for a long-anticipated sabbatical, my first as I begin my 18th year in the rabbinate, that will begin in mid-June and conclude toward...

HEALTH & WELLNESS

Fitness

Swimming

Tennis & Pickleball

More Sports

EDUCATION

Jewish Culture & Education

Early Childhood Program Preschool

After School & Childcare

Camps

ARTS & CULTURE

Literary Arts

Visual Arts

Theatre & Film

Dance

COUNSELING & SUPPORT

Jewish Family Service

Counseling & Groups

Case Management

References & Resources

Copyright Shalom Austin 2023. Privacy Policy.